HOW WIN REMMERSWAAL BECAME THE FIRST EUROPEAN-TRAINED MAJOR LEAGUER

EEN MOOI ARTIKEL OP MLB.COM DOOR MEGAN WARD ISM BURTON DS

HOW WIN REMMERSWAAL BECAME THE FIRST EUROPEAN-TRAINED MAJOR LEAGUER

The Red Sox were losing, 4-1, to the Brewers in the sixth inning when manager Don Zimmer made the call to his bullpen for a skinny right-hander who had just been brought up from Triple-A Pawtucket.

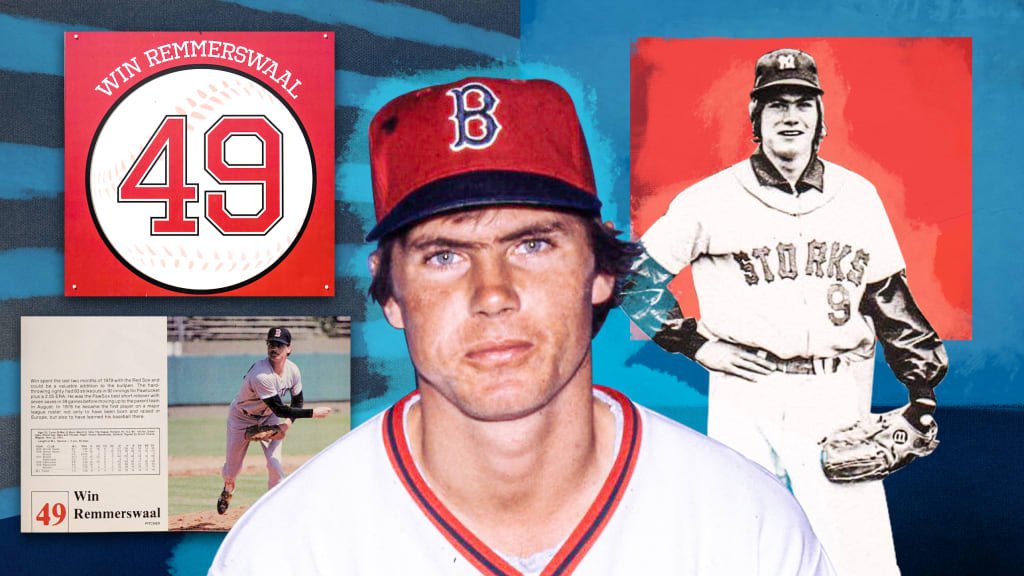

Few among the crowd at Milwaukee County Stadium recognized the name, Remmerswaal, stretching across the back of the 25-year-old’s jersey. His nickname, however — short for Wilhelmus — was a word eminently familiar to any baseball fan: Win.

It was an inauspicious moment for a Major League debut, further overshadowed by all the baseball world had on its mind on Aug. 3, 1979. The tragic death of Yankees captain Thurman Munson covered the front pages of newspapers, and Red Sox fans were counting down with bated breath as Carl Yastrzemski inched closer to 3,000 career hits.

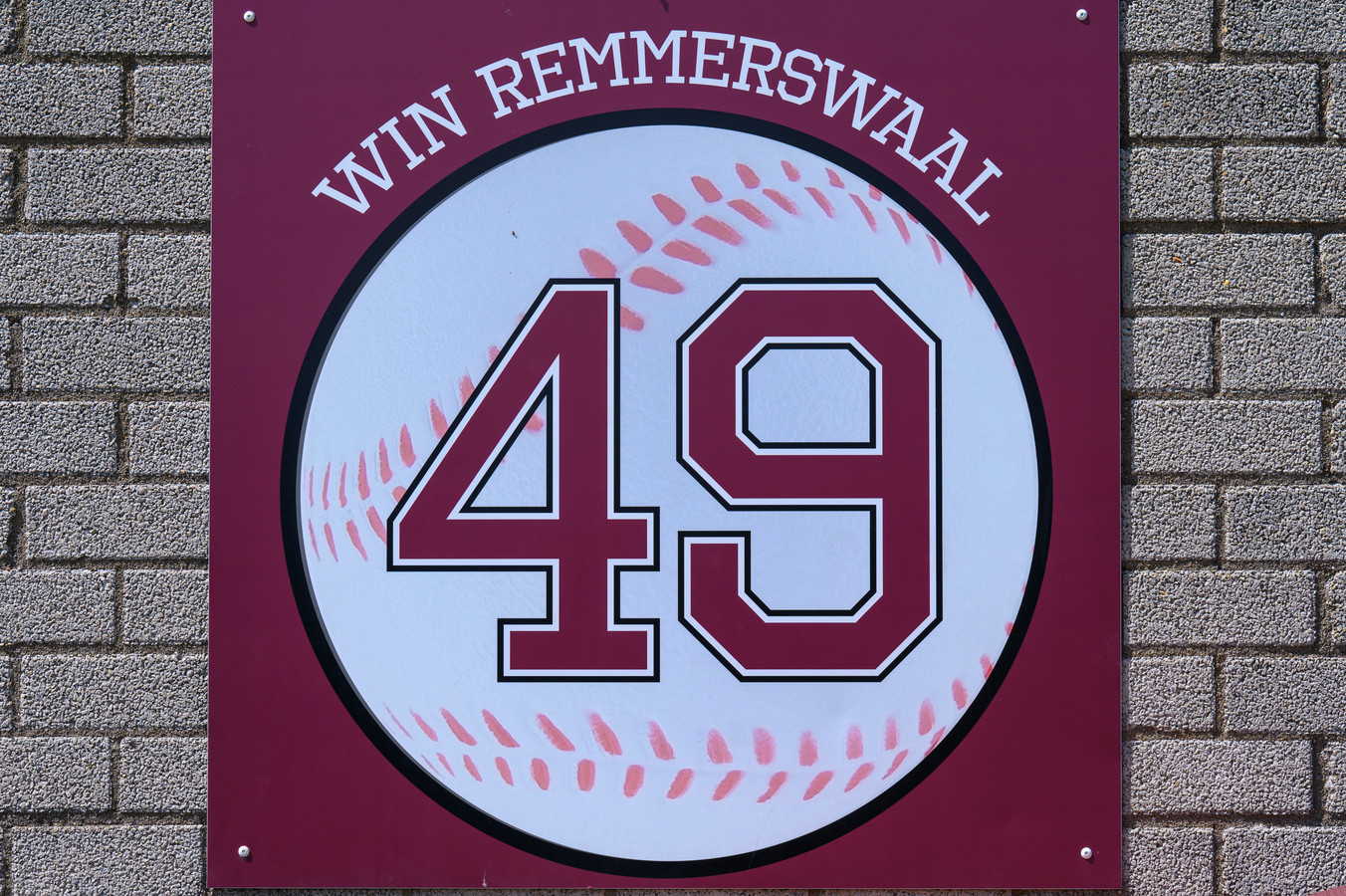

Win Remmerswaal would not come close to reaching any such milestone in his brief and injury-plagued big league career. But by the time he induced a double play from the first batter he faced, he had carved out a place in baseball history. Born and raised in the Netherlands, Remmerswaal had just become the first European-trained Major Leaguer.

*****

Remmerswaal excelled at sports from a young age. Growing up alongside three athletic brothers in Wassenaar, a suburb of The Hague, he played soccer in the winter and baseball — or as it’s known in the Netherlands, honkbal — in the summer.

“Win was a good soccer player and played until his 18th [birthday],” Wil Koot, a childhood friend, said in an email, “but he was passionate about baseball.”

Remmerswaal and Koot’s houses lay just 200 meters from the athletic fields. Their local baseball team held practice several times a week. Every Wednesday, they played clubs from the American Baseball Foundation consisting of children of American expats. But that wasn’t enough for the baseball-obsessed Remmerswaal.

“During our holidays we were always on the field throwing to each other or having batting practice,” Koot remembered. “Even when we went to high school, he was waiting for me afterwards to have some practice. … Only a few guys occasionally spent time practicing after school or during holidays, but none of them were [as] uniquely passionate and driven as we were.”

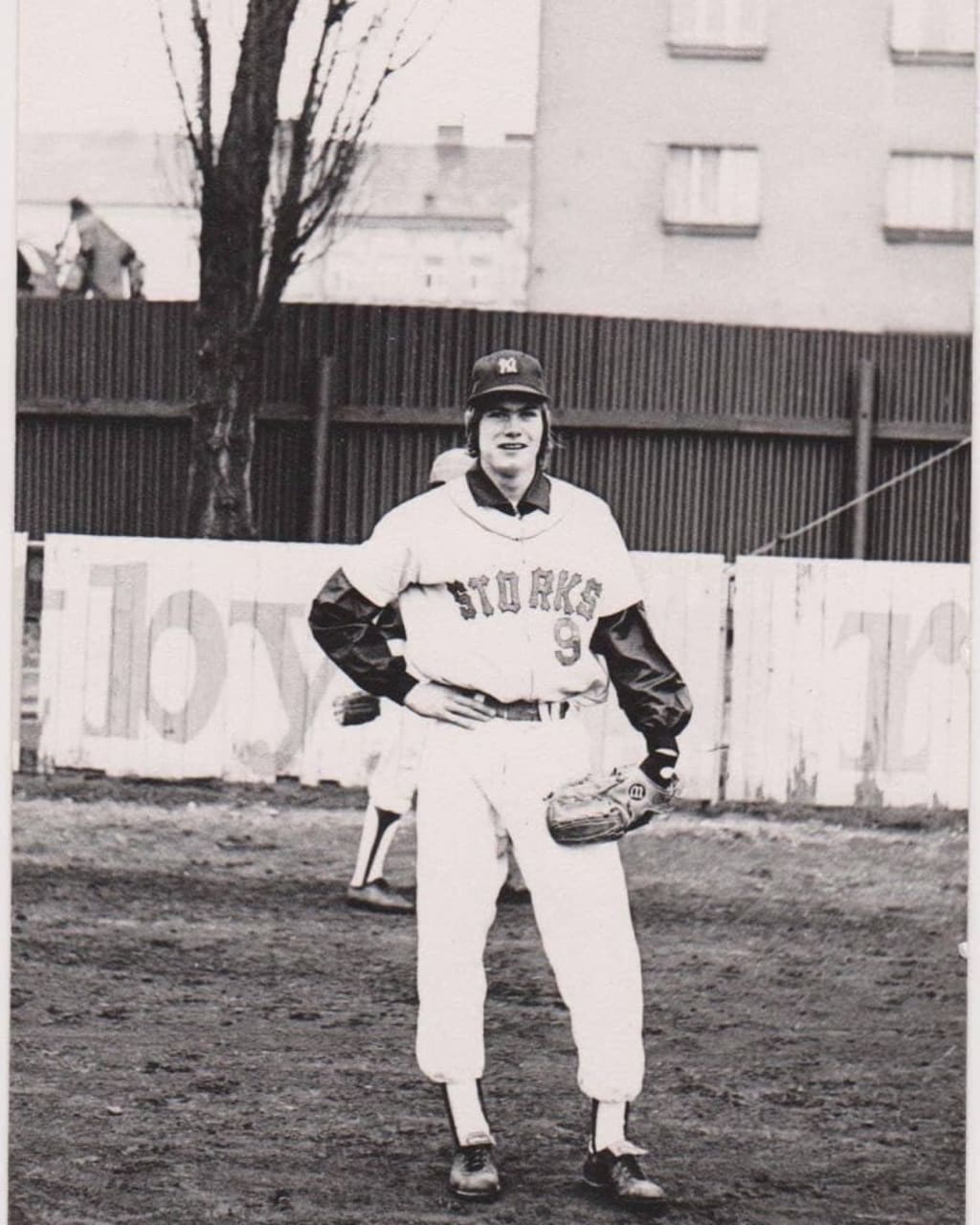

By the time Remmerswaal was in his late teens, his talent had garnered the attention of the Storks, a team belonging to the highest level of professional baseball in the Netherlands — the Honkbal Hoofdklasse.

“He was the best pitcher in Europe at the time,” said Storks hurler Frank de Groot.

Despite being in the Dutch big leagues, the Storks remained largely a family operation. Players had to purchase their own equipment and uniforms, and parents helped out with laundry. But on game days, thousands of spectators filled the stands to watch the Netherlands’ best, including the boy from Wassenaar whose arm awed both the crowds and his teammates.

de Groot recalled a time he was warming up with Remmerswaal:

“Just prior to the game, he says, ‘Frank, you stand on home plate, and I go to first base, and I start throwing to you. And in the meantime, I’ll walk backwards.’ … He ended up almost at the fence in the outfield.”

Remmerswaal came to be known as much for his idiosyncratic habits as his immense talent. He chewed tobacco, more like a Major Leaguer than a honkballer.

“That’s a special one,” said de Groot. “Nobody in Holland chews tobacco.”

Remmerswaal often seemed to be off in his own world, forgetting things or arriving late to the ballpark. This tendency would take an amusing turn in the Majors. Remmerswaal once overslept before a game in New York, hailed a taxi and found himself miles away from Yankee Stadium at Shea Stadium, where the Jets were playing a football game.

Another time, according to Thomas Boswell’s How Life Imitates the World Series, Zimmer once called to the Sox bullpen to “get Win up” and was told he was out in the stands buying peanuts. But Remmerswaal’s abilities made up for his absentmindedness.

“He wasn’t the typical pitcher, listening to the coaches,” de Groot said with a laugh. “But OK, he’s throwing 50 strikeouts per game, so you’re excused.”

In the 1973 European Championship, Remmerswaal pitched for a Dutch national team that steamrolled its way to a third straight title. After allowing just two hits and two walks while striking out nine over 6 2/3 scoreless innings in a come-from-behind win vs. Italy, he was named the tournament’s best pitcher.

“He had … good moving stuff, control, and his leg was very flexible,” said de Groot. “Throwing this inside moving stuff, going and breaking down.”

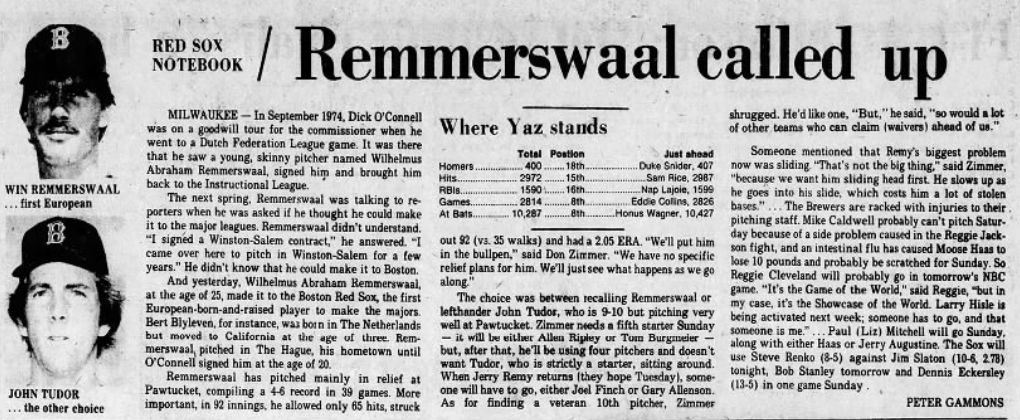

As Remmerswaal continued to play, he attracted attention from outside Europe, namely Major League scouts. One of them was Red Sox general manager Dick O’Connell, who signed him to a professional contract on Nov. 22, 1974.

This marked a significant achievement for the boy who had dreamed of playing in America since his early teen years and for the country that had trained him. Future Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven, born in Zeist, Netherlands, made his MLB debut in 1970, but he had learned the game in California. Now, a Hoofdklasse player had a chance to play baseball on the biggest stage in the world.

“I didn’t think a Dutchman would make it to the Major Leagues,” Koot admitted. “For us, this was only a dream — the spare pieces we saw on television of Major League Baseball were millions of miles away.”

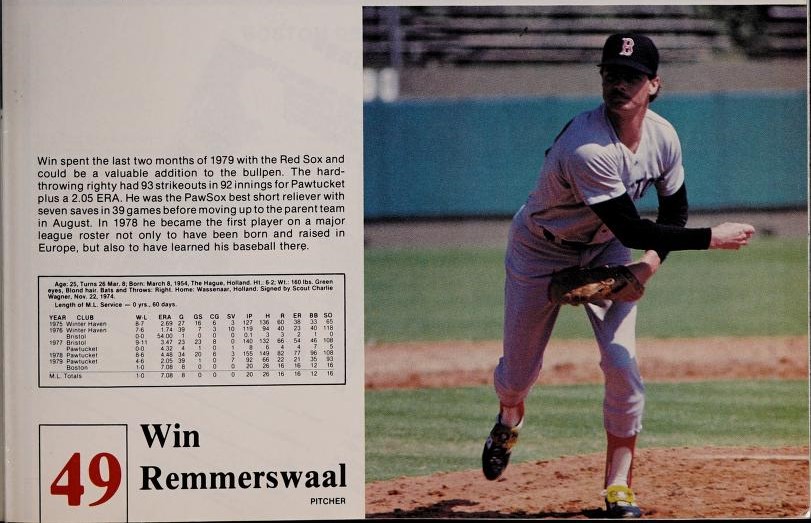

In his first three seasons in the Minors (1975-77), Remmerswaal climbed from Single-A Winter Haven to Triple-A Pawtucket, recording a 2.76 ERA with 296 strikeouts over 94 games (47 starts). He attended big league Spring Training in ‘78 but spent the season in Triple-A, where he went 8-6 with a 4.47 ERA in 34 games (20 starts).

Despite his success, pitching in the Minors required adjustments for a player trained in Europe.

“Every pitch I use has been changed in the past three years, since I started playing professional baseball,” Remmerswaal told The Boston Globe in 1978. “They started me all over again, from the beginning.”

Remmerswaal began the 1979 season in Triple-A, but in August he got the call. According to his SABR bio, in typical Remmerswaal fashion, the right-hander stayed in bed, ignoring the knocks on his door for so long that the team had to reschedule his flight to join the Red Sox on their road trip.

Two days after his debut, he recorded his first career win in a 19-5 Sox blowout.

Remmerswaal wasn’t convinced that anyone back in the Netherlands cared much, telling Peter Gammons of The Boston Globe that baseball was “such a small thing there, I don’t even know if I made the papers.”

He was wrong.

“There was a lot of effort and a lot of news around the Netherlands,” said Ton de Jager, a former Storks infielder and board member. “It was in the paper, it was on the radio, on the TV. And I think it was opening doors for the next generation to see if they can succeed in the States.”

Sticking in the Majors, however, is an altogether different beast than getting there. So effective for much of his Minors career, Remmerswaal struggled to a 7.08 ERA with 12 walks to 16 strikeouts over eight outings for the Red Sox in his debut season.

The next year, after skipping winter ball in Puerto Rico due to a shoulder injury, he posted a 2-1 record with a 4.58 ERA over 14 games for Boston.

Remmerswaal was the last reliever to appear for the Red Sox that season, getting two outs in the top of the ninth on Oct. 5. It would be the 26-year-old’s final Major League outing.

Remmerswaal returned to Pawtucket in 1981, etching his name in the history books once more, this time as one of the pitchers in a 33-inning marathon that remains the longest recorded professional baseball game. Still troubled by shoulder problems, his frequent stints on the injured list exacerbated the loneliness he often felt in America. He began to drink more. Eventually, he was outrighted by the Red Sox and returned to Europe after playing in just 22 MLB games.

Remmerswaal found some success on an Italian team and served as head coach for the Amsterdam Pirates in Hoofdklasse, but he continued to be plagued by health problems and addiction. After complications from pneumonia he contracted in 1997, the man who had spent the first four decades of his life on a baseball field was confined to a nursing home.

By the time Remmerswaal passed away in 2022 at the age of 68, few remembered the eccentric righty who had broken new ground for Europeans in the Majors.

Among younger generations in the Netherlands, interest in baseball has declined and Remmerswaal’s story has faded into obscurity. It has been some time since a player followed in his footsteps from Hoofdklasse to the Major Leagues. Perhaps the Cardinals’ No. 13 prospect, Sem Robberse, a Zeist native, is next.

“You don’t see it too often that somebody from the Netherlands has a shot at making it into the big leagues,” Robberse told MLB.com. “It’s really cool to also see, like, the former players that are from there. It’s a small country, and to have some of the players go [from] over there is pretty cool. …

“I would love to be able to represent in some way. When I have the chance and the opportunity to, I definitely would love to grow the game, especially over there in Europe and in the Netherlands.”

There’s a symmetry in the two right-handers, separated by half a century, paving a path for their country in Major League Baseball.